SESSION 4.

SESSION 4. THE MARKETS OF THE MAFIA.

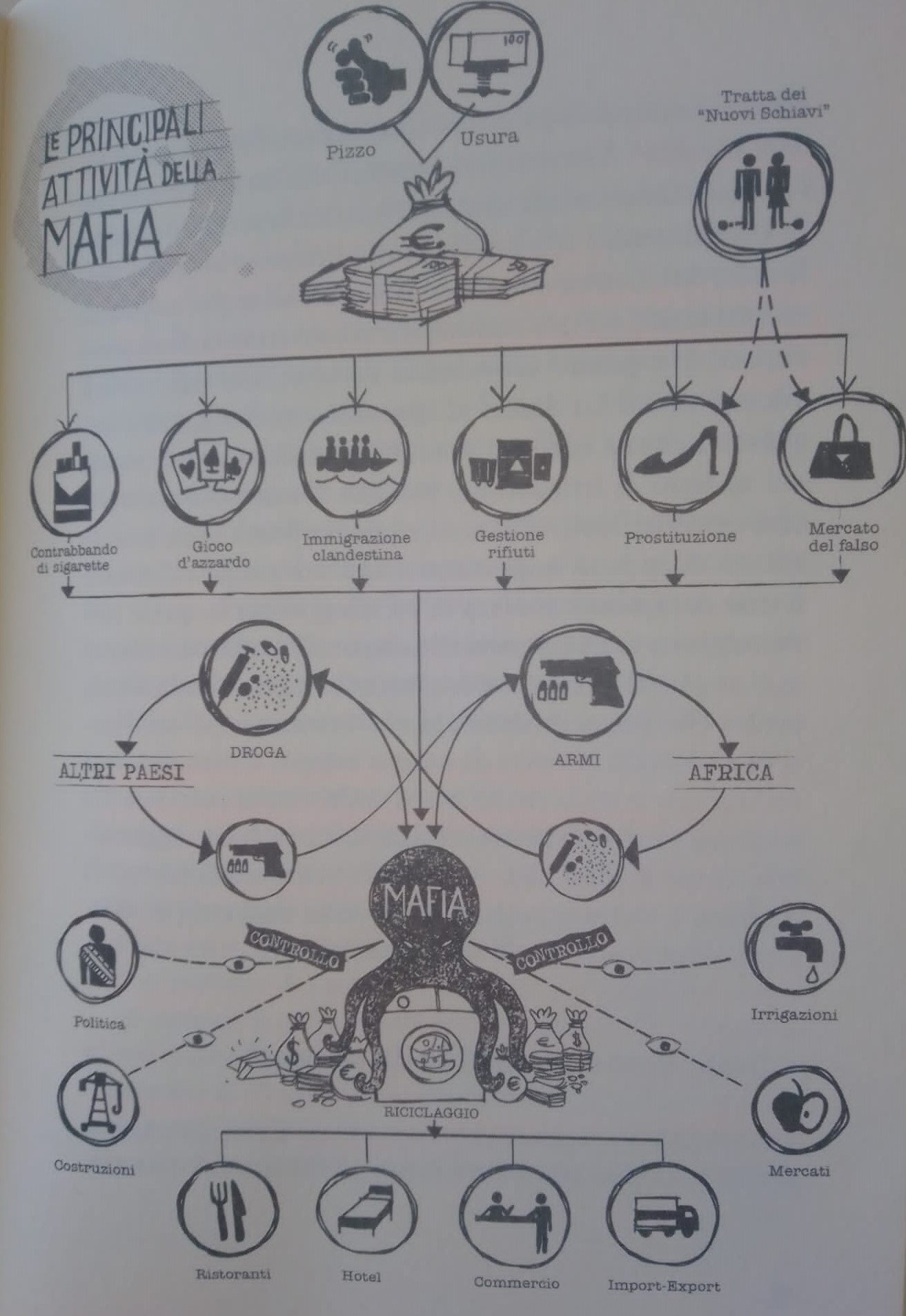

The markets mafiosi. The mafia, to generate as much profit as it does, controls and works within various markets. Here we will see them, isolated, but often these markets are interconnected with each other.

Figure 1. Nicaso, Antonio. “La mafia spiegata ai ragazzi”. Arnoldo Mondadori, 2010. pg. 49.

AGROMAFIA AND CAPORALATO.

Agromafia. It refers to all of the illegal activities carried out in the agricultural sector (“Agromafie e Caporalato” 1, Chiabrando 4). This includes all of the various processes in the agricultural industry going from the agricultural production to their transformations and arrival in the ports, from the markets to the grand distribution, from the packaging to the commercialization of products (Chiabrando 4).

Revenues and statistics. According to the 2015 report on agricultural crimes in Italy, there has been an influx in the profits the agromafia generates, going from 14 billion euros in 2013, to 15,4 billion at the time of the report. It is an increase of at least 10% which has been caused by both internal and external factors, such as climate change that diminished the agricultural products and the diminishing bank loans and credits to various enterprises (Montante and Saso 14, 65, 95, 141).

Olive Quick Decline Syndrome (OQDS). In 2013, in a zone of Puglia where there are many olive groves and a chain of hotels, the bacterium Xylella fastidiosa is found, affecting 6 billion olive trees and 8 billion hectares of terrain (Montante and Saso 19-20). The bacterium is a deadly one that destroys olive trees. While the State has given financial support to the region and the affected agricultural industries the loss it will continue to provoke is far greater. What is very strange about this whole situation is that when investigations started, in 2013 to try and understand the causes of the OQDS the bacterium was stated to be just found, when actually there are reports that state the bacterium’s presence back in 2010 but clearly not much attention was given as that was hidden and the bacterium was able to spread exponentially in the three following years (Montante and Saso 25). Another curious thing is that while there was an importation of the pathogenic germ of the Xyellela in Bari to study and experiment, no bacteria was found in the olive trees surrounding Bari, only the ones in the zone of Gallipoli, where the chain of hotels are, 200 km from Bari (Montante and Saso 26).

Figure 2. Martelli, G.P, and Boscia, D., and Porcelli F. and Saponari M. “The olive quick decline syndrome in south-east Italy: a threatening phytosanitary emergency”. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 8 october 2015.

Centro Agroalimentare di Roma (CAR) - the food industry of Rome. Within the CAR, illegal work and exploitation has been observed for a total of 1,500 individuals per month, some of which are minors. Many of these are immigrants, many of whom are Egyptian, who are undocumented and work at a very low cost, augmenting to a total of 150 to 250 euros per month (Montante and Saso 31). The minors, once reach the CAR have their documents taken away and get exploited as they have to pay back the cost of the travel to get to Italy, totally up to an average of 10,000 euros (Montante and Saso 32).

Caporalato. A phenomenon that dates back to the second world war, mainly known in the agricultural sector. It refers to the exploitation of braccianti, workers, that under the control of the a caporale, an intermediary figure between the workers and the land owners that manages the work of the braccianti. The braccianti often work in the fields, picking crops such as tomatoes, peaches and watermelons. They get salaries below the minimum wage (between 25 and 30 euros daily), aboutely no insurances and inhumane hours of labor that can reach up to 12 hours daily on the fields picking crops. The figure of the caporale has only been criminalized in 2011 with the law n. 138 entitled “Illegal intermediary and labour exploitation”, later reformed in 2016 into the new law n. 199. The newest update on a plan to contrast the caporale has been introduced on 20 february 2020 which is based on a two year plan to try and prevent, monitor, contrast, protect, assist and reintegrate the braccianti (Villafrate, “Agromafie e Caporalato” 1- 3, Mangano).

- What can you do on an individual basis to support a legal, environmental-friendly and human-rights-friendly agricultural market?

Figure 3. Salzano, Roberta. “Rapporto tra caporalato e riduzione in schiavitù.” Cronache di ordinario razzismo, 24 septembre 2019.

Figure 4. Moramarco, Mimmo. “Caporalato, parte in Puglia la filiera etica”. Le cronache, 11 april 2019.

The Km zero or farmers’ markets. There is a reduction of prices as the products are produced within 70 km of the location in which it is sold. This also means there is a reduction in the emission of CO2 associated with transportation. If you think about it, 1 Kg of kiwis imported from New Zealand to Italy travels 18 thousand Km and emits 25 Kg of CO2, 1 Kg of peaches from Argentina to Italy travels 12 thousand kilometers and emits 16 kg of CO2 (Montante and Saso 164). It is also suppose to guarantee the quality and freshness of the products that do not have to be packaged, labeled, and are grown according to its agricultural season (Montante and Saso 163). This market however does not guarantee the dignity of the worker.

Fair Trade, mercato equosolidale. The World Fair Trade Organization (WFTO) defines fair trade as a “trading partnership, based on dialogue, transparency and respect, that seeks greater equity in international trade. It contributes to sustainable development” and largely focuses on the “marginalized producers and workers, especially in the South”pole (Mehta, “Il Commercio Equo e Solidale”). The WFTO has set out 10 fundamental principles for becoming a fair trade organization;

- creating opportunities for economically disadvantaged producers;

- to deal fairly and respectfully with trading partners and all stakeholders;

- concern for the social, economic and environmental wellbeing of marginalised small producers;

- payment of a fair price;

- ensuring no child labor and forced labor;

- no discrimination based on race, caste, nationality, relgion disability, gender, sexuality, political affiliation, HIV/AIDS status of age;

- ensuring good working conditions

- increase development for small producers by developing their skills and capabilities;

- raising awareness of Fair Trade and the possibility of greater justice in world trade;

- respect for the environment (Mehta, “Il Commercio Equo e Solidale”).

Worldwide, there are 355 Fair Trade Enterprises that “impact 965,7000 livelihoods, 74% of whom are women” (Mehta). In Italy, the major Organization of Fair Trade is Altromercato which is formed by 105 associates and 225 stores. It trades with 155 organizations of producers in over 45 countries (“Chi siamo”).

Made in Italy and forgeries. A major activity that the mafia controls is the forging of the Made in Italy and in the origin of the product, in the agricultural field. The three main products that are commonly forged are; olive oil, tomato products, and prosciutto. While the EU regulation n.1169/2011 obliges the indication of the origin of the product and the art. 4, comma 49 and 49-bis of the law n. 350 of the 24 december 2003, protects the Made in Italy, the mafia has infiltrated the market to forge both of these regulations and gain profit (Montante and Saso 29, 145-6). For example, olive oil will be smuggled into Italy from other countries, primarily Spain and Greece, within the EU, and the MENA region, in particular Tunisia and Turkey, outside of the EU (Montante and Saso 37, 63, 72). Tomatoes will be smuggled from Tunisia, Morocco and the Canaries Montante and Saso 38). The meat to make the prosciutto, some comes from Chile (Montante and Saso 46). They will then be sold at a much higher price, altering the quality on the labels and its place of origin (Montante and Saso 37, 53-4). This, in addition to being illegal, can be harmful for the consumer that might be buying very low-quality products (Montante and Saso 54, 60, 76). In fact, in the operation “Bufale Sicure”, investigating mozzarelle di bufala from the region Campania, 7 farms were found to produce infected milk and mozzarelle in bad conservation states (Montante and Saso 60). The false Made in Italy has been found to accumulate 60 billion euros in the global market, which is double of the revenues of the Italian export of agricultural goods (Montante and Saso 149).

- Policies have been made to hold actors accountable and inspections are taking place, but this seems to not be enough. What measures can be taken to counter and prevent this illicit market?

Restaurants. With the economic crisis, the mafia has stepped in and offered security and an opportunity for investing and expanding, by becoming partners with the company. This is a great way for money laundering (Montante and Saso 57). The report estimates there are approximately 5,000 restaurants/bars in the hands of the mafia in Italy (Montante and Saso 58). In march 2014 five restaurant/bars in Rome, with a value of over 6 billion euros, were seized in the investigation “tramonto” (Montante and Saso 59).

FALSIFICATION OF PUBLIC CONTRACTS (APPALTI TRUCCATI).

Public contracts. It is through these that the State guarantees the realization of the infrastructures and other needs the society might have. It is a fundamental instrument to the development of the società (Spartà 25). According to the Public Procurement Indicators of 2014, Italy spends around 169.8 billion euros annually, a total of 10.5% of its GDP (Spartà 26).

The mafia’s infiltrations. Public contracts are perfect for the mafia as they create both a mean for money laundering and monetizing the illegal activities into legal ones, but also it generates much profit from public spending and the services such contracts later provide (Spartà 26). Infiltration in public contracts is also good as it gains power within the territory as it provides jobs and services for many, generating consensus and legitimacy within the society (Spartà 27-28). It is punishable by the article 353 of the penal code which invisions a fine going from 103 to 1.032 euros and incarceration for six months to five years (Spartà 27).

The grey area, l’area grigia. The associates of the mafia that corrupt and make deals with politicians and administrators work within what is referred to as “area grigia”, grey area. And this has in large part replaced the violent means previously used by the mafia to achieve its wanted outcomes (Spartà 28). It is a strategy that took over most of the public contracts in the late 1980s in Sicily with cosa nostra corrupting to falsify public contracts. It was revealed in a trial which gave the name Metodo Siino, Siino method, to this tactic and soon became the method used in the rest of Italy to falsify public contracts (Spartà 30-31). This process today has become much more complex with various actors specializing in either the execution of the activity, the technical-professional realization of the illegal activity and finally the intermediary that takes care of the negotiations between mafia and institutional actors (Spartà 32-35).

EXPO 2015, Milan. A concrete case in which there was the infiltration of the mafia within a public contract is the one of EXPO 2015, in Milan, a project that generated 260 million euros annually (Spartà 37,44, Sasso). In july 2016, eleven people were arrested do the the infiltration mafiosa, of cosa nostra, within the EXPO. The pavilions of the palazzo congressi, the auditorium, France, Qatar, Guinea and the stand of Poretti Beer had been altered. Fiera Milano delegated the realization of the EXPO 2015 with international advertisements and financial support, dictated by Nolostand. Nolostand put Dominus in charge of constructing the EXPO, which was administered by “teste di legno”, but actually could be traced back to two individuals, Giuseppe Nastasi and Liborio Pace, associated with the mafia (Sasso).

Figure 5, 6. “EXPO 2015 Milan - guide de pavillons, ce qu’il faut voir et comment s’y rendre”. Vie nocturne Guide de la ville, 6 may 2015.

COUNTERFEIT (CONTRAFFAZIONE).

Counterfeit. It is the act of falsifying or imitating fraudulently. This can go from the previously discussed agricultural Made in Italy, to the clothing and fashion statements Made in Italy, to technological softwares, CDs and DVDs, to toys, to mediations (Chiabrando 4-5, Micara 54). The crime of counterfeit damages the companies as they are unable to sell all their products. It damages the State and its society as it results in tax evasion and hence fewer services and it overall alters the functioning of the economy. It exploits the most vulnerable (Chiabrando 4-5, Gulino 45). In Italy it is estimated to generate 6 billion and 900 million euros annually, according to a report published by CENSIS (Gulino 45).

MEDICRIME. It is an international convention that obliges the various states to implement legal restorative action when it comes to the forging of medications (Micara 69). This because the forging of medication is primarily a transnational issue and it is one that can have detrimental effects on the health and lives of people (Micara i.g).

Countering the counterfeit. Industries, to try and protect their products from being copied and falsified, should first and foremost attain a patent from either the State, the EU or international entity, that allows the temporary right of monopoly on a certain invention. In continuation, an industry should also create its own brand that allows for the identification of a good and its origin. If a good is seen to have been counterfeited, it is the industry’s responsibility to denounce the violation as to allow the guardia di finanza and the customs agency to step in and take economic and retributive consequences (“Contraffazione e falso”).

GAMBLING.

Means for money laundering and extortions. The infiltration of the mafia within the business of gambling of course generates a consistent amount of revenue. It is estimated that for every apparatus that has been taken by the mafia, it generated around 1,000 euros per every week it is used (Torrigiani 14). Gambling however is even more convenient for the mafia as it is also used as a means for money laundering. It is also used however to foster their other business of extortion as once one has used up all their money in gambling, they go to various clans to ask for more money which they will then have to repay with an enormous interest. (Torrigiani 5-6, 11).

The mafia’s infiltration. The high demand for gambling has allowed for the penetration of the mafia within the sector and its evolution towards online platforms has further facilitated the mafia within the sector (Torrigiani 5). Gambling is a business that globally, in 2016, generated 470 billion dollars (Torrigiani 7).

The State. Gambling in Italy is controlled by the State (Torrigiani 11).

Antimafia and its solutions. In july 2016, the team Antimafia proposed five points to the Parliament regarding how to contrast the mafia in the gambling business which were approved. The five points are the following; 1) more barriers for entrepreneurs to enter the gambling business, 2) a revision of the penal and administrative sanctions making them tougher, 3) the reinforcement of the measures against money laundering, tracing all the revenues, 4) the reinforcement of antimafia politics and 5) a new governance of the sector (Torrigiani 29-30).

HUMAN TRAFFICKING AND THE SMUGGLING OF HUMANS.

The difference between human trafficking and smuggling. While these two phenomenons are very similar, they have their differences. Human trafficking entails the recruitment and illicit transport of people with the scope of exploitation, many times sexual or labor exploitation (De Zulueta 7-8, Santino). Such exploitation can also, however, take other forms such as the trafficking and selling of organs (Pangerc 76). The smuggling of humans also works with illegal transportation and favoring clandestine migration, but it does not entail the exploitative end. It is important to note however that while these two phenomenons are distinct, many times it is very hard to draw the line as the smuggling of migrants does not guarantee an exploitative-free process (De Zulueta 7-8, Santino).

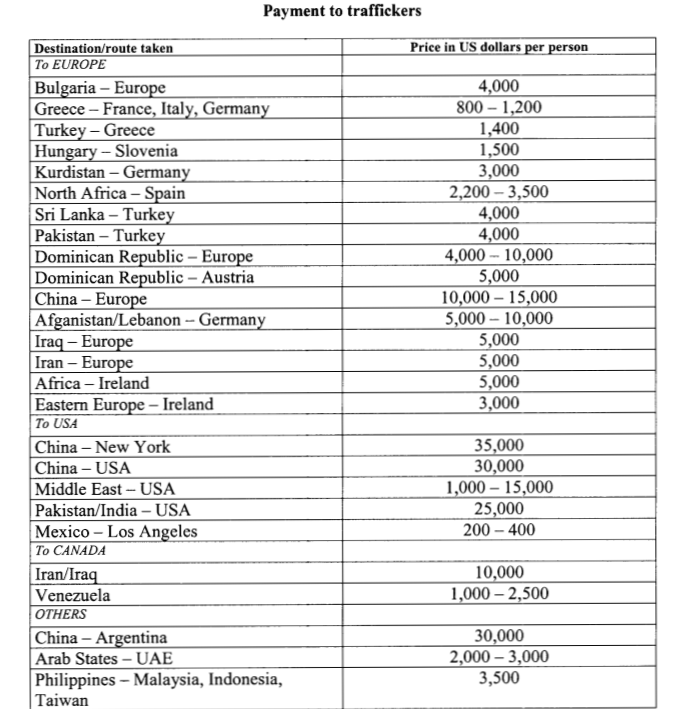

A profitable business. Both human trafficking and the smuggling of people are business that generate much revenue. This is because the price that has to be paid by an individual to be able to get transported illegally is very high, as shown in the table below (De Zulueta 11-12). The revenue however is not just used for personal gain, but it is also used to corrupt officials, bureaucrats, politicians and law enforcement. Nonetheless, it generates a revenue of 31 billion dollars annually, making it the third largest business controlled by criminal organizations, after narcotrafficking and the trafficking of arms (Santino).

Figure 7. International Organization for Migration, Migrant trafficking and human smuggling in Europe, Geneva, 2000.

A transnational phenomenon; Ad hoc. It is extremely important to analyze the relation between the mafia and human trafficking/smuggling using a trannational approach as it is a phenomenon that knows no borders. It is a process that starts with the small criminal organizations in the country of origin to then intertwine those of the country of transition and lastly the country of destination. For instance, there are the criminal organizations from Eastern Europe, the Albanian, the Bosnian, the Nigerian, the Turkish, the Russian and the Chinese mafie, to name a few, that collaborate to allow for this phenomenon to continue (De Zulueta 21, 23, Pangerc 31). These groups of local criminal organizations and new forms of mafia are what the Italian national Antimafia have named Ad hoc in 1997 (Pangerc 31). What is interesting is that each Ad hoc specializes in a certain nation they will traffick or smuggle. For example, the turkish mafia focuses on the illegal migration of the curds while the Nigerian mafia focuses a lot on the trafficking of Nigerian women for sexual exploitation (Pangerc 33). Many times, the criminal organizations that organize the transportation of people, simountanelsy transport drugs, tobacco and weapons, such as the Turkish, Chinese and Russian mafie (Pangerc 35).

- Due to the complexity of this trade and the interconnectedness of various local and international criminal organizations, who should be in charge of taking effective measures and how? Should it be the State, NGOs, IGOs or others who carry out such measures? What allows for such trade to continue? Is an undertanding of the root causes of human trafficking and the smuggling of people necessary for the implementation of effective responses? If so, how?

Additional information. To know a bit more about the extent to which it is fundamental to have an understanding of the root causes of the Nigerian human trafficking in Italy as to allow for effective responses, here is the link to my Extended Essay tackeling the question:

ILLEGAL CONSTRUCTION (ABUSIVISMO EDILIZIO).

What it implies. Illegal construction, or abusivismo edilizio, implies the illegal construction of structures and is synthesized by the terms ciclo illegale del cemento, the illegal cycle of concrete. It is illegal for many reasons. First and foremost, it is illegal because the construction takes place without authorization and in some cases it happens on lands that are dangerous and highly susceptible to earthquakes and floods. For example, in 2018, after very heavy rains, the river Milicia, in Sicily, flooded, provoking the death of 10 people, of which 9 were in a villa that had been illegally constructed and flooded (“Maltempo, tragedia a”). It is also illegal because, following the scope of building as much as possible spending the least possible amount, many times the concrete that is used is not of good quality and mixed with other ingredients that further increase the danger of such construction (“Abbatti l’abuso”, “Il ciclo illegale”). There have been cases, in fact, where toxic waste was mixed within the concrete, provoking what journalists refer to as “sick-building syndromes” - cancers and illnesses for the families that later moved into those structures (Gatti). Lastly, illegal construction also implies the re-emergence of the phenomenon of caporalato in which the workers all work illegally with a minimum pay, if any at all, and no protection at all (“Abbatti l’abuso”).

Figure 8. Bonfardino, Rosaura. “Maltempo, tragedia a Casteldaccia, esonda il fiume Milicia: 9 morti”. Monreale press, 4 november 2018.

Its statistics. According to the 2019 report of Legambiente, the illegal cycle of concrete has gone up by 68% in 2019, from 3,908 crimes in 2018 to 6,578 crimes in 2019 (“Il ciclo illegale”). It is estimated, in fact, that every year this illegal market produces more than 20 thousand houses (“Abbatti l’abuso”).

Earthquakes. Italy is geographically placed in an area susceptible to earthquakes and the infrastructure in Italy is not built accordingly so once earthquakes occur it usually ends up with many deaths and much destruction. The mafia uses this for its own benefit, falsifying public contracts aimed at the reconstruction of cities and villages (Spartà 38).

Figure 9. “Séisme en Italie: la ville d'Amatrice attaque Charlie Hebdo”. L’est Républicain, 25 november 2016.

- To what extent is the use of irony acceptable to highlight the infiltration of the mafia within a context that has provoked much sufferance and losses? Does the actor using the irony matter?

The campaign ‘Abbatti l’abuso’, ‘Fight the abuse’. This campaign, launched by Legambinete aims at demolishing the structures that have been constructed illegally. While at first it might provoke some resistance, especially from those that bought those houses and are living in them, but the idea is that by demolishing these a strong message of law and order is passed, slowly altering the culture and conception of illegal constructions to be deemed illegal, immoral and harmful to both humans and the environment (Biffi and Fontana 4-5).

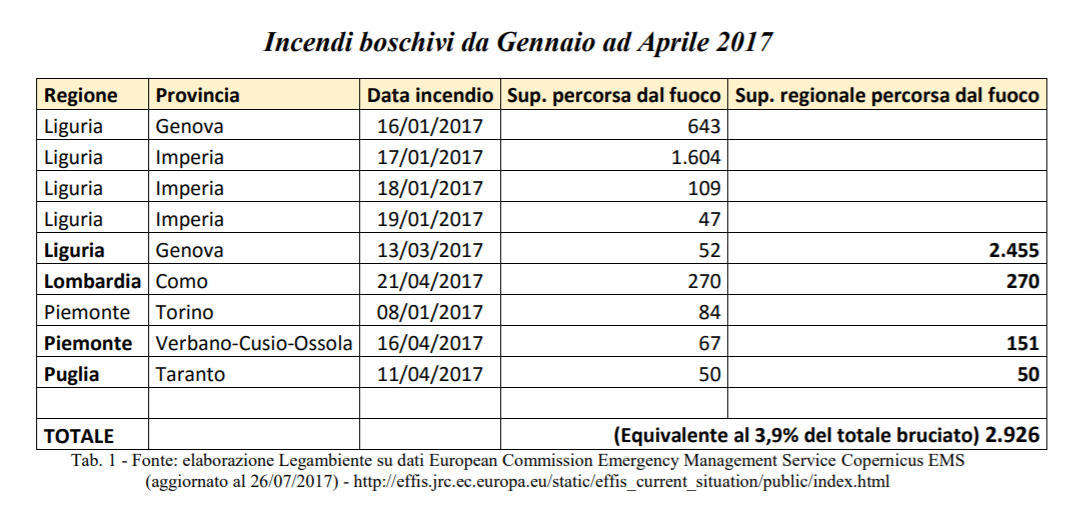

Manmade fires, forests burn. How does the mafia pursue its businesses in lands that are occupied or protected by the government? They burn it down. “Every summer Italy burns”. Only in 2016 more than 27,000 hectares of forests and green areas have been burned by 4,635 arsons, incendi dolosi. This data has doubled since the previous year which saw 2,250 arsons. The damage brought in 2016 augmetns to 14 million euros while the costs to extinguish the fires were around 8 million euros (“Dossier Incendi” 3, Galullo). These extensive environmentally-damaging actions have however been criminalized as an ecocrimes by the law n. 68 in the Italian penal code passed in 2015. And some cases have been tried and condemned, showing progress in the justice system (“Dossier Incendi” 4). What is interesting is that although these fires would be sparked in the summer, they are now also being initiated in winter, with the region Liguria being at the top of arson in the winter months. This is shown in figure 10.

Figure 10. “Dossier Incendi 2017”. Legambiente, 27 july 2017, pg 14.

Figure 11. Costa, Sergio. “L'Italia brucia per mano dell’uomo: sono dolosi gli incendi che stanno distruggendo i nostri boschi”. Greenme, 2 august 2020.

INDUCEMENT TO VOTE.

The right to vote. In Italy it is in 1882 that the right to vote is extended to all males above the age of 21 having completed elementary school (Melissari 49). It is however only in the 1970s that the mafia changes positions in regards to the State and decides that is much more convenient making affairs with it (Melissari 65). That is precisely when the mafia starts to have greater power in the inducement to vote, exchanging money or favors for votes, but also in the infiltration of administrative positions, being themselves elected (Melissari 49). In fact, there have been many communal administrations that were dissolved as found to be associated with the mafia (Melissari 75, Saviano 2011). There has also been evidence showing how, for example, in the 2010 elections in Campania, one voter was given 50 euros to vote for a specific candidate (Melissari 78). This is one of the clearest examples of how the mafia has not only infiltrated the economic sphere, but also the political one, in which we see politicians buying their votes from the mafia through corruption, protection and guaranteed services, such as the falsification of public contracts (Melissari 59). Precisely because politicians do not only buy votes from the mafia with money, but rather also favors of other kinds, the Italian jurisdiction has a problem as it only punishes and condemns, in the art. 416 ter c.p., the exchange of money for votes (Melissari 7, 61). Figure 12. Melissari, Laura. “Il voto di scambio e il voto di preferenza: il caso della Calabria”. Libera Università Internazionale degli Studi Sociali, 2012-2013. pg. 61.

Clientelism. Clientalism is defined, in political terms, as “the relationship between individuals with unequal economic and social status (“the boss” and his “clients”) that entails the reciprocal exchange of goods and services based on a personal link that is generally perceived in terms of moral obligation” (Briquet). There has been studies, such as those of the academic Fantozzi, that have compared the mafia to clientelism as they both exercise power. The difference lies in the way in which these exercise power in their favor; the first uses physical violence as well as social and territorial control, while clientelism focuses on an exchange between patron and client which have similar private interests (Melissari 60).

KIDNAPS.

Many scopes. While kidnaps have become much more rare by part of the mafia, it nonetheless persists. While it may seem like the only scope of a kidnap is to obtain money, kidnaps many times were much more than just an end. The many means kidnaps played were the following; 1) distracting law enforcement from other much more important markets and routes, 2) vengeance or part of a faida, a war between different families of clans. Kidnaps saw a big boom in the 1970s, provoking the introduction of new laws, such as the law n. 497 passed in 1974 condemning and punishing kidnappers, later modified to augment the time of incarceration. Law n. 82, passed in 1991 is one of the newest laws regarding kidnaps and allows the blockage of the goods of those sharing blood with the individual that has been kidnapped as to impede the payment of the ransom and discourage kidnaps (Fischetti).

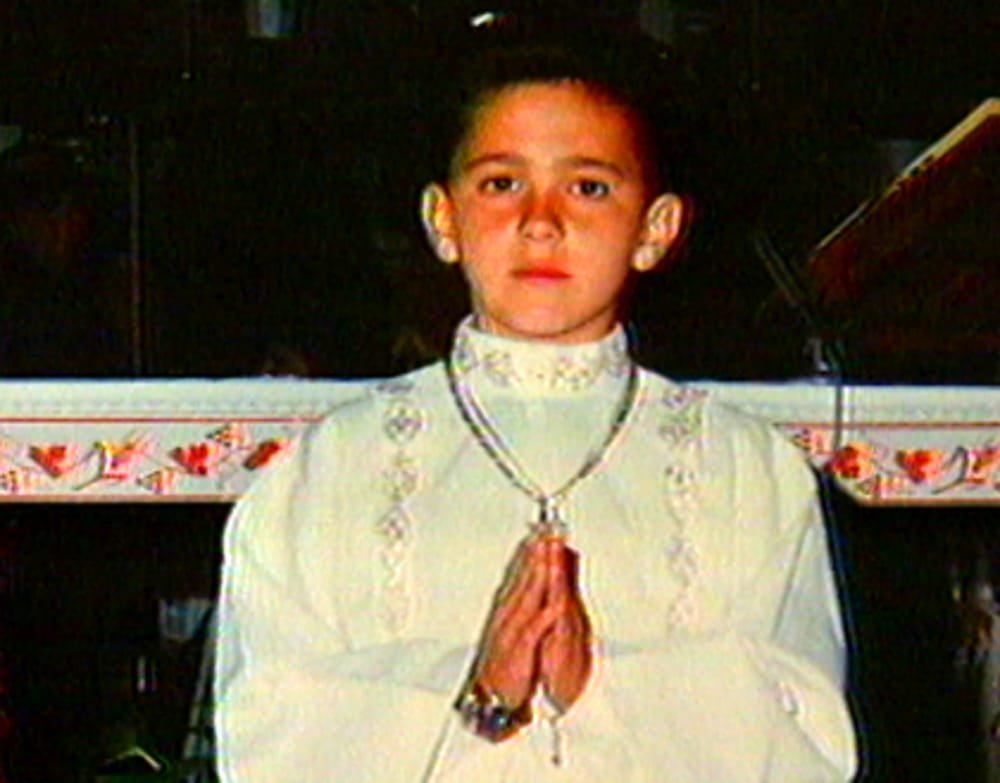

Giuseppe Di Matteo. In 1996, the adolescent Giuseppe Di Matteo is killed by his kidnappers, affiliates of cosa nostra. He was strangled and melted in acid without pity. This is because it was an act of vengeance. Giuseppe was the son of santino Di Matteo, a member of cosa nostra that had been arrested in 1993 and had started to collaborate with the justice system, saying the names of those that had provoked the attacks and the judges Falcone and Borsellino. These types of atrocious homicides, to show their potence and ferociousness, following a kidnap, have been named “lupara bianca” or “white shotgun” by journalists (Fischetti, Lupi).

Figure 13. Lupi, Federica. “A boy and the mafia”. B. History, 6 september 2019.

NARCOTRAFFICKING.

Trafficking. There are many ways to transport drugs. In Italy, many drugs come by sea, hence arrive in the ports, in big containers. Some drugs however also arrive by plane, via individuals who are called “backpackers” or “ovulatori”, which ingest ovules containing drugs and are supposed to eject via the anus once arrived at destination. The problem is that if one of the ovules explodes while inside the individual, the person dies of overdose (Tatarelli, Saviano 2014). Saviano, in his book Zerozerozero also talks about the ways in which drugs are trafficked, tracing predominantly cocaine, coming from South America into Naples. In addition to the people that ingest the ovules of drugs he also refers to how food, for example, bananas are used to hide the drug and transport it, unnoticed at the borders (Saviano 2014).

Figure 14. “Ingerisce oltre un chilo di droga, arrestato”. Il Tirreno, 15 december 2018.

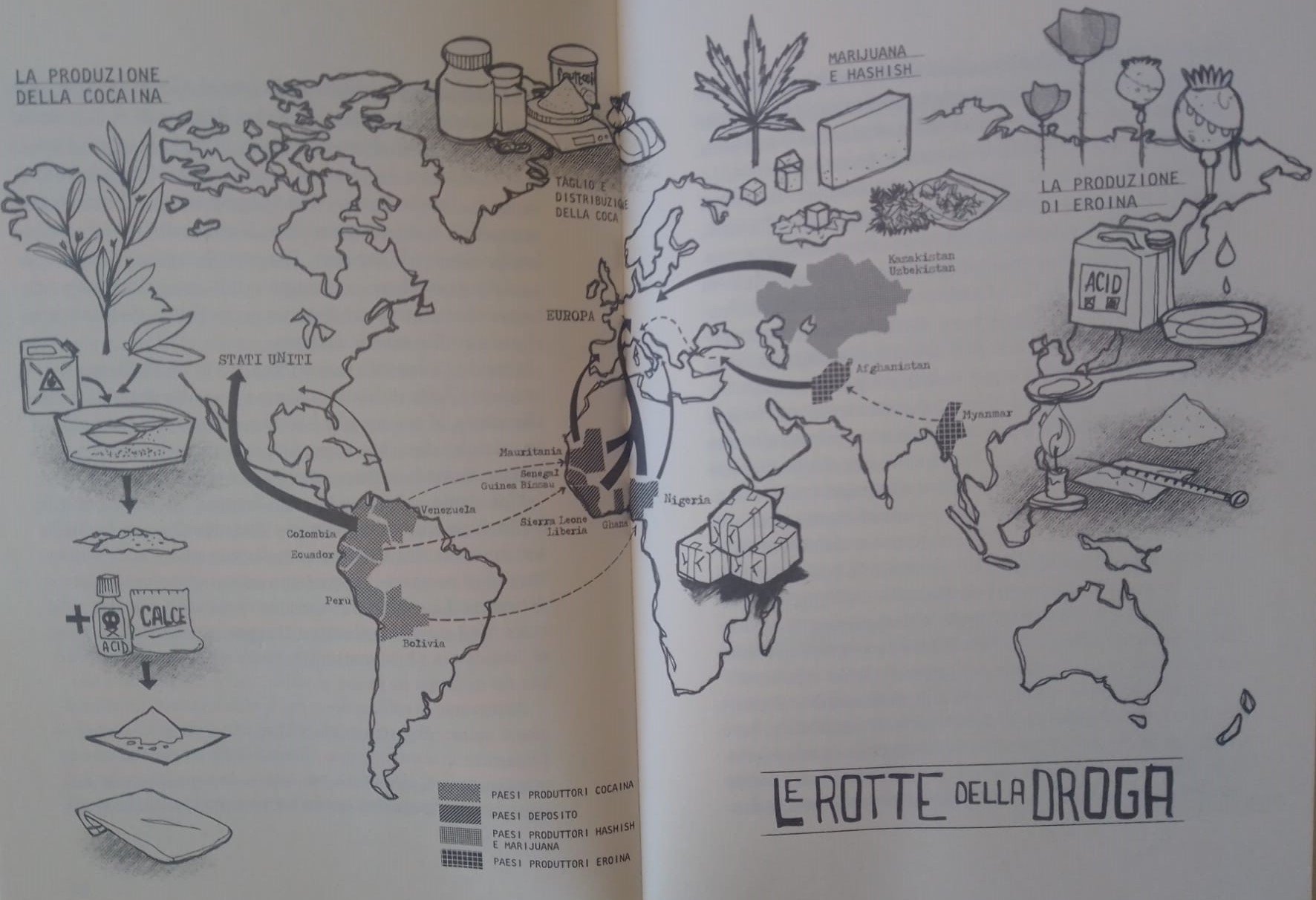

Production. There are various places of production, of which each tends to focus on a particular drug. Cocaine, for example, is predominantly produced in Latin and South America. While initially it was the various cartels in Colombia, notably the cartel de Medellin, that had monopoly on the production, refinement, transportation and distribution of the cocaine, today it is a market that has expanded and they no longer have full monopoly. Now, in competition with the cartels of Colombia there are the cartels of Mexico to which compete and the production of cocaine in Peru. The competition has allowed for the further expansion of the market, developing new technologies to make it more efficient, such as the genetic modification of the color of cocaine plants in Mexico as to make it more difficult to individualize (Tatarelli). It is in the 1990s that the ‘ndrangheta first comes into contact with the colombian cartels and makes deals to internationalize the cocaine market (Giannini 11). Italy however also greatly imports cocaine from the neighboring Spain and Netherlands, with the help of the Albanian mafia. Heroin and opium, on the other hand, is primarily produced in Afghanistan (Tatarelli).

Figure 15. Nicaso, Antonio. “La mafia spiegata ai ragazzi”. Arnoldo Mondadori, 2010. pgs.52-53.

Distribution. While Italy is a country of consumption for both cocaine and heroin, it is also a country of transition, like Turkey and Iran, for the trafficking of heroin to northern Europe (Tatarelli). What is interesting is that the drugs that stay in Italy, while being fully controlled by the Italian mafie, are not only distributed by the Italian mafie but also by small external criminal groups, in particular Romanians, Tunisians, Moroccans and Egyptians. Hence, we here see the use of emigrated criminal groups being used for marginal roles (“Doc XXXVIII” 534).

Revenue. The ‘ndrangheta controls 80% of the cocaine that arrives in Europe and hence generates a revenue of 46 billion euros annually (Bongiovanni).

PROSTITUTION.

Prostitution in Italy. In 1958 with the law Merlin, regulated prostitution becomes forbidden and the ‘houses of pleasure’ or ‘bordelli’ banned. Prostitution in Italy, while in itself is not deemed a crime, becomes a crime in three situations; 1) when there is a third party involved that exploit, 2) when there is the favoring of prostitution, and, 3) when one is induced into prsotituion. Prositution in itself is deemed a crime only when there are minors involved, as states in the art. 600 bis of the Penal Code (Bellitto).

Human trafficking. As previously mentioned, much of the prostitution in Italy is the result of human traffciking for sexual exploitation and hence many of the prostitutes are of Nigerian origin (Pangerc 33, Minniti). Once in Italy, these women, oftentimes also minors, get terrorized by their maman - women that accompany them and manipulate them through voodoo or juju rituals. Because this business generates much revenue, there is a tight collaboration between the Nigerian and Italian mafie (Minniti, Carletti). In 2016, there were around 5,000 women trafficked into Italy for sexual exploitation, augmenting to a total of around 150 million euros in that year (Minniti). A great movie to understand more about this phenomenon is Òlòtūré on Netflix, which is based on a true journalistic investigation.

- According to the jurist Massimo Kunle D’Accordi, and because prositution in Italy has a lot of the prostitutes coming from other countries, as long as there will be politics related to migration, tough national laws that impede migrants from obtaining documents that allow them to find a lawful job, prostitution will remain high, controlled by international mafie (Carletti). To what extent do you agree? What could other obstacles that favor the continuation of prostitution in Italy? What can be done to eliminate prosittution, or at least, the illegal aspect and control of it?

RACKETEERING (EXTORTION AND PIZZO).

Racketeering. It refers to the wider umbrella of “acquiring a business through illegal activity, operating a business with illegally-derived income, or using a business to commit illegal acts”. In simpler terms it encompeses crimes such as bribery, money laundering, gambling, robbery, and extortion, to name a few (Seth).

Extortion and pizzo. An extortion is the means used by the mafia to affirm power and control over the territory as it is a form of exchange between the mafia and the people. The mafia receives money, the pizzo, as a way for the people, in particular, small businesses and entrepreneurs, to have guaranteed protection from the mafia (Rizzuti 1, 5, Spartà 29, Chiabrando 4). It is important to note that this exchange is possible due to the lack of the State able to guarantee for the protection of its people (Rizzuti 1). Extortion is the oldest form of revenue used by the mafia as it is profitable and efficient, lasting in the long-run as it established territorial control and fear, creating dependency between the entrepreneur and the mafia (“Estorsione”, Rizzuti 1). Once that is established and the pizzo is regularly given to the mafia, the entrepreneur may be additionally involved in the mafia, having to hide some of their merchandise or use their own business as a coverup for their money laundering or other activities (“Estorsione”). Extortion is a crime punishable under article 629 of the Penal Code (Rizzuti 3).

Countering policies. The academic Alice Rizzuti distinguishes between two different types of policies put in place to counter the extortion racket. The first are the direct policies, such as the augment of protection for the collaboratori di giustizia, the adoption of preventative patrimonial measures. The second are indirect policies, including those set up to create a culture of legality, such as benefits for the victims of extortion, measures aimed at improving the socio-economic development of the regions and more rigorous controls of business to assure they are mafia-free (Rizzuti 8-9).

- Which policies do you think are most effective in countering the rackets of extortions and pizzo and hence should be the focus of those drafting policies? Why?

Addiopizzo. Another initiative that has been introduced, to counter the culture of the pizzo is the association Addiopizzo, meaning literally ‘goodbye pizzo’. Founded in 2004 by some of the youth of Palermo who took the initiative of putting flyers all over the city on which was written “An entire nation that pays the pizzo is a nation without dignity” (Rizzuti 30). This brings the attention of the people who start to realize the damage the pizzo does to them and presents the final aim of protection the article 41 of the Constitution stating that it is everyone’s right to exercise freely their private economic initiatives, without being obstacolated by the mafia (Rizzuti 31). Since this first initiative, the association has brought forth many other initiatives creating more sensibility in regards to culture of legality. They have brought forth ‘I pay who doesn’t pay. Against the pizzo change the consumption’, which is an initiative that incentivizes the consumption towards the businesses and entrepreneurs that have rebelled and denounced the mafia and its extortion (Rizzuti 32). In 2007 Addiopizzo directed a project towards the youth, going into schools and sensibilizing the children on these topics (Rizzuti 33). The association has also been present in many courtrooms to denounce and demand compensation for the damage caused by the extortions, guaranteed in the article 74 of the code for penal procedures (Rizzuti 42).

Additional video. If you speak Italian, watch the following video for an anecdote and a testimony who decided to refuse and denounce the mafia when asked for the pizzo, in 2020.

Libero Grassi. It is not easy to decide to not pay the pizzo and denounce the mafia, as that can be at the cost of one’s life. Libero Grassi, the 29 of august 1991 is killed by cosa nostra because he refuses to pay the pizzo. In the picture to the left, Addiopizzo commemorates his death and his fight against the mafia (“Mafia: 27 anni”).

Figure 16. “Mafia: 27 anni fa omicidio Libero Grassi, Addiopizzo 'contro racket poche denunce'”. Antimafia Duemila, 21 august 2018.

SMUGGLING OF CIGARETTES, TOBACCO AND OTHER MERCHANDISE.

Smuggling of cigarettes or tobacco-related products. It is defined by article 1 of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), put forward by the World Health Organization (WHO) which states that is is any practice or behavior that violates the law and relates to the prosecution, transportation, possession, distribution, selling or buying of tobacco, including any practice or behavior that facilitates these activities (Angelini and Calderoni 93).

Low risk, high profit. The reason why this activity is so appealing to the mafia is indeed its low risk and high profit. This is because, unlike other illegal markets that generally deal with goods and services that are deemed to be immoral, this market deals with an activity that is either illegal or unusual. Cigarettes are also heavily taxed, consumed and relatively easy to transport as they also have an interesting relationship with its weight and value (Angelini and Calderoni 93). In Italy, this activity has become big again since the 90s. Most of the cigarettes come from Eastern Europe - Poland, Hungary, Czeck Republic, Slovakia, Romania and Bulgaria - where cigarettes are bought legally, one packet for less than a euro, and then smuggled into Italy and sold illegally by the camorra or ‘ndrangheta. Most recently, the smuggling of cigarettes in Italy does not only come from Eastern Europe but from China as well, with the use of the Internet and the committing of cybercrimes (Chiabrando 5).

THEFTS.

Thefts. It is the action of appropriating a good that is of someone else’s ownership, through the use of threat or violence (“Le rapine” 77). There was a decrease in thefts since the 90s and now even though they have increased, it is not the mafia’s major source of revenue (“Le rapine” 86). In total, the damages provoked by thefts are of 1,6 billion euros while 2,1 billion euros and used for protecting equipment such as alarm systems (Chiabrando 4).

TRAFFICKING OF WEAPONS.

Trafficking of weapons. The UN Protocol against the production and trafficking of illegal weapons, their parts, components and munition for the illegal market defines this illegal market as the importation, exportation, acquisition, selling, transporting of the illegal weapons and their part from one country to another without authorization from the States involved. What is interesting about this market is that the arms and their parts are not just a source of revenue for the mafia but also essential weapons for their other criminal activities such as narcotrafficking. Weapons and their munitions are long-lasting and easily stocked and hidden. They can be used even after decades of acquiring it (Camerini 88). Most of the weapons that the mafia in Italy deals with or comes in contact with are the ones coming from Eastern Europe, the Balckans and Turkey (Camerini 88, 91). Turkey takes the weapons from the unstable regions of the Middle East and traffic them to Europe (Camerini 92). In Italy, it is estimated that in 2010 the illegal market of weapons augmented to a revenue of 46,7 million euros and that these weapons represent 8-10% of the total weapons commercialized in the country (Camerini 89).

USURY.

Usury. It is often referred to as an illegal loan or strozzinaggio, literally choking someone. It is the act of loaning money via illegal channels with a high interest rates to a person or an enterprise who usually has economic difficulties. Why do associations mafiose bother taking part in this risky market? One might think that they do not have the means of guaranteeing the return of the money, with its elevated interests, but actually they do. They use no only violent and intimidatory tactics to get back the loaned money plus its interests, they also can take a quota or the entire capital of the enterprise and take possession of it, as has been done by the ‘ndrangheta with the business Perego. Secondly, usury is very much linked to other illegal markets as the money that is being lent often is the revenue of other illegal markets that is used to recycle it and infiltrate the legal market. The borrowed money however does not all enter the legal market but is sometimes also used in other illegal markets, in particular drugs and gambling (Salha and Riccardi 120).

Times of crisis. Oftentimes the mafia in the usury market flourishes in times of economic crisis as desperate families and businesses go to them to borrow money. This was seen after the 2008 crisis and can be seen today, in 2020, with the covid-19 pandemic (Salha and Riccardi 121).

Ethical issues. A very interesting thing to note is that while some groups such as the camorra have always been involved in this illegal market, other associatiaons mafiose such as cosa nostra actually only ethically accepted this market, as well as the one of prostitution and gambling, at the beginning of the 80s (Salha and Riccardi 120).

Revenues. The way in which the revenues of usury have been calculated are indirect, such as calculating the number of victims to be those enterprises that have been refused a loan from the bank (Salha and Riccardi 121). Studies conducted from judicial inquiries have calculated a total of 4 million and a half euros worth of revenue for various clans mafiosi throughout Italy from 2014 to 2016, who ask interest that go from 40 to 400% annually and from 16 to 200% monthly (Torrigiani 6).

SPECIAL CASE STUDY: COVID-19 AND THE MAFIA.

Seizing the opportunity. As we have previously seen with the example of the earthquakes, moments of crisis and tragedy does not retain the mafia from its businesses and rather, it provides the perfect opportunity for the mafia to profit, steal from State resources and have less forces putting pressure on it. The pandemic has allowed for the expansion of the mafia’s infiltration within the pharmaceutical industry and has greatly infiltrated all those businesses that are now necessary due to the ongoing pandemic, such as all the sanitation and cleaning services, funeral services, and distribution of food, to name a few. The drug market also saw a boom in the time right before the lockdown, with an augment in the consumption of drugs, most likely due to the idea of being confined, as speculated by Saviano. What Saviano, points out, is that the pandemic is not just beneficial for the mafia’s economy but also for their power as there are fewer efforts put forward for the fight against the mafia and silence prevails. This is because the current issue that has to be dealt with is the virus. It might also be, however, because the mafia has stepped forward in places where the State lacked an efficient response, and hence the mafia is providing a system of welfare, with food and loans at much lower interest rates than usual. As a consequence however, once the pandemic is over, the entrepreneurs that got some sort of support from the mafia will have to repay their debt and that is why Saviano urges States to immediately give out financial help to those that need it as to prevent the further strive of the mafia once the pandemic has become under control (Saviano 2020, Pipitone e Trinchella).

An interesting investigation. A journalist from Vice News went to Naples to investigate how the “business is booming for the Italian Mafia during Covid”. The most interesting sections of this investigation are the following; from 2:05 to 3:50, then from 7:08 to 9:50 and then from 11:04 to 11:46.

WORKS CITED.

“Abbatti l’abuso”. Legambiente.

“Agromafie e Caporalato”. Flai-CGIL Nazionale. pgs. 1-4.

Angelini, Monica and Calderoni, Francesco. “Traffico illecito di prodotti del tabacco”, in From illegal markets to legitimate businesses: the portfolio of organised crime in Europe Final Report of Project OCP. Transcrime – Joint Research Centre on Transnational Crime, 2011, pgs. 93-101.

Bellitto, Simone. “Prostituzione in Italia: è reato in quali casi? E in quali no?”. lentepubblica, 22 october 2019.

Biffi, Laura and Fontana, Enrico. “Il manuale d’azione di Legambiente”. Legambiente, 18 october 2012. pgs. 3-18.

Bongiovanni, Giorgio. “Narcos e mafia: i criminali più potenti della Terra”. Antimafia duemila, 28 february 2020.

Camerini, Diana. “Mercato illecito delle armi da fuoco” in From illegal markets to legitimate businesses: the portfolio of organised crime in Europe Final Report of Project OCP. Transcrime – Joint Research Centre on Transnational Crime, 2011, pgs. 88-92.

Carletti, Gabriele. “"Vi dico chi sfrutta traffico di droga e prostituzione. E come affrontarlo"”. TGR Trento, 18 january 2020.

Chiabrando, Danilo. “Mafia ed economia: un intreccio pericoloso”. Para mond. pgs. 1-5.

“Chi siamo”. Altromercato Impresa Sociale Soc. Coop.

“Contraffazione e falso Made in Italy”. Camera di commercio Milano Monza Brianza Lodi.

De Zulueta, Tana. “Commissione parlamentare d’inchiesta sul fenomeno della mafia e delle altre associazioni criminali similari”. Camera dei deputati, Senato della Repubblica, doc. XXIII, n. 49. 5 december 2000, pgs. 7-96.

“Doc XXXVIII”. Camera dei deputati, Senato della Repubblica, n. 4. pgs. 529-544.

“Dossier Incendi 2017”. Legambiente, 27 july 2017, pgs. 2-24.

“Estorsione (racket e pizzo)”. Antiracket.info, Federazione delle Associazioni Antiracket e Antiusura Italiane.

Fischetti, Laura and Chiara. “Quando le mafie facevano i sequestri di persona”. La Repubblica, 5 septembre 2018.

Galullo, Roberto. “Perché la mafia dei terreni incendia l'Italia”. Il sole 24 ore, 13 july 2017.

Gatti, Antonietta. “Il moderno cemento? Tossico, oltre che fragile”. La Stampa, 7 novembre 2017.

Giannini, Fabio. “La mafia e gli aspetti criminologici”. Centro Ricerca Sicurezza e Terrorismo, Pacini Editore Srl 2019, pgs. 4-49.

Gulino, Loredana. “Contraffazione e criminalità organizzata”. GNOSIS, n. 35, pgs 41-57.

“Il ciclo illegale del cemento. I numeri del 2018”. No Ecomafia, Legambiente, 2019.

“Il commercio equo e solidale”. Altromercato Impresa Sociale Soc. Coop.

“Le rapine” in Rapporto sulla criminalità in Italia. Analisi, Prevenzione, Contrasto. Ministero dell’interno, pgs. 77-110.

Lupi, Federica. “A boy and the mafia”. B. History. 6 september 2019.

“Mafia: 27 anni fa omicidio Libero Grassi, Addiopizzo 'contro racket poche denunce'”. Antimafia Duemila, 21 august 2018.

“Maltempo, tragedia a Casteldaccia, esonda il fiume Milicia: 9 morti”. Monreale Press, 4 november 2018.

Mangano, Antonello. “Agromafia e caporalato: un glossario”. terrelibere.org, 23 april 2019.

Mehta, Roopa. “About us”. World Fair Trade Organization.

Melissari, Laura. “Il voto di scambio e il voto di preferenza: il caso della Calabria”. Libera Università Internazionale degli Studi Sociali, 2012-2013. pgs. 4-104.

Micara, Anna G. “Falsificazione di medicinali, criminalità organizzata e cooperazione internazionale”. Cross, vol. 2, n. 2, 2016. pgs. 54-82.

Minniti, Federico. “Prostituzione, così le mafie fanno affari per 150 milioni di euro l’anno”. Angensir, 17 october 2017.

Montante, Susy and Saso, Raffaella. “Agromafie 3° Rapporto sui crimini agroalimentari in Italia”. Eurispes, january 2015. pgs. 11-223.

Pangerc, Desirée. “Migrazioni illegali e traffico di esseri umani: le rotte balcaniche - il caso Bosnia-”. Dottorato di ricerca dell’Università degli Studi di Bergamo, 2009-2010. pgs. 1-315.

Pipitone, Giuseppe and Trinchella, Giovanna. “Coronavirus, i progetti della mafia per sfruttare l’emergenza: “Sostegno a famiglie in difficoltà, caccia ad aziende in crisi e manovre per truffare pure sugli aiuti pubblici. Ritardi dello Stato? Ne approfittano i clan””. Il Fatto Quotidiano, 12 may 2020.

Rizzuti, Alice. “Misure di contrasto al racket estorsivo: il ruolo della società civile e l’esempio di Addiopizzo”. Università degli studi di Pisa, 2013.

Salha, Alexandre and Riccardi, Michele. “Usura” in From illegal markets to legitimate businesses: the portfolio of organised crime in Europe Final Report of Project OCP. Transcrime – Joint Research Centre on Transnational Crime, 2011,pgs. 120-123

Santino, Umberto. “l mercato del sesso a Palermo. Mafia e nuovi gruppi criminali”. Centro Siciliano di Documentazione "Giuseppe Impastato" - Onlus.

Sasso, Michele. “La mafia dentro i padiglioni di Expo 2015”. L’Espresso. 6 july 2016.

Saviano, Roberto. “Coronavirus, perché la mafia vuole prendersi prende cura dei nostri affari”. la Repubblica, 26 april 2020.

Saviano, Roberto. Gomorra. Edizione Oscar Mondadori 2011. pgs. 1-373. ISBN 978-88-04-66423-9.

Saviano, Roberto. Zerozerozero. Giangiacomo Feltrinelli Editore Milano 2014. 1-444 pgs. ISBN 8807885417.

Seth, Shobhit. “Racketeering”. Investopedia, 1 july 2020.

Spartà, Sara. “Appalti pubblici e criminalità organizzata”. Cross, vol. 2, n. 3. 2016. pgs.24-45.

Tatarelli, Luca. “Traffico di droga, il modus operandi della criminalità organizzata. Il Nord Europa Hub dell’afflusso degli stupefacenti”. Report Difesa, 11 september 2019.

Torrigiani, Filippo. “Gioco sporco, sporco gioco. L’azzardo secondo le mafie “. Coordinamento Nazionale Comunità di Accoglienza (CNCA), november 2017. pgs. 1-40.

Villafrate, Annamaria. “Il caporalato”. Studio Cataldi, il diritto quotidiano, 2 march 2020.

The PDF for this session can be found here:

The power point presentation can be found here: